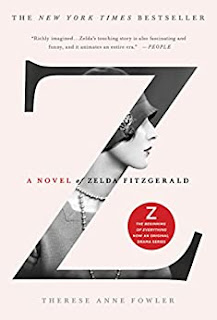

Zelda: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald

By Therese Anne Fowler

Not long ago, a friend gave me a bag full of books. That's sort of like Christmas morning to me. What treasures were there?

Not long ago, a friend gave me a bag full of books. That's sort of like Christmas morning to me. What treasures were there?The first one that caught my attention was Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald.

This is not a new book - it was published in 2014. But since when has that ever meant much in the world of fiction?

I was in high school when I first read an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, The Great Gatsby, probably one of, if not the most accessible of his books and thus a good introduction to his writing for a high school student.

Two main things struck me: his prose was delightful, and his characters were despicable, except for perhaps, Nick Carraway. Oddly enough, it was this novel - the one now hailed as one of the greatest American novels - that began his slow decline into failure, alcoholism, and ultimately, an early death.

In each of his other novels, Fitzgerald was simply playing his own life out on paper, offering some excuses for "his" character, and blaming things on his lost (real) first love, Ginevra King, and later his wife, Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald.

More than that, of course, was the theme of "us against them," the "youth vs. age," and the Jazz Babies vs. the Old Guard, that permeated his writing. This, no doubt, appealed to the young teachers of the 60s, who found common ground with the introspection of a writer like Fitzgerald.

What's all this got to do with a book about Zelda, his wife, the spoiled youngest child of an old and wealthy southern family, notorious party girl and later an institutionalized supposed schizophrenic?

After all the novels Fitzgerald wrote in which his wife's character played a major role, and all the examinations of his writing and him as a man that reflected on her influence, and the several biographies of her that have tried to understand her within the scope of her relationship to her famous writer husband - here is a novel that digs into her heart and soul in a way that is both fizzy and easy to read, but at the same time, sees life through her eyes.

A problem, of course, for any writer tackling a fanatically covered subject like the Fitzgeralds, will be finding something new, fresh, insightful or distinctive to say about her characters.

Surprisingly, here is a fresh take on the woman who often takes the lion's share of the blame for the decline and fall of a Great American Author. The story is written in the voice of Zelda, and for the most part, it works. Early on, the voice is girlish, flirtatious, and uses "gonna" and "s'pose" and even a sweet Southern drawl that drips honey and privilege.

Following her near-miss affair with a Latin lover, when Scott has been inattentive and even jealous of her own literary efforts, there is a sudden shift in the style of her voice, and in the focus of the narrative. We are introduced to a tougher, more no-nonsense, even "feminist" voice, that actually made me stop, back up a few pages, and be sure I hadn't missed anything. I'm still not sure if I think it was a brilliant writing move, or if the author was determined to "make a case" for Zelda.

Scott and Zelda were the "it" couple of the 20's. The very epitome of the Jazz Babies - all youth, vigor, self-indulgence, glamour and not a lot of common sense. They drank, spent, danced, "flipped off" their elders, cut their hair and their hemlines, and roared the twenties to the maximum. If the expression take it to 11 had been around then, it would have been 12. They knew all the right people, and lived in all the hot places. It was only when Scott thought Zelda had been unfaithful (not just merely desirable) and when, at least according to this interpretation, he fell under the sway not just of money, his agent, and alcohol, but other writers - notably Hemingway - that he began to see her as an adversary, rather than his joined-at-the-hip ally.

As for Zelda, and this much appears to be history, she desperately wanted to shine as something other than the woman that hung off the arm of Scott Fitzgerald. Fowler uses her artistic license to give Zelda a real dose of artistic ambition, wanting to write and paint as well as her famous addiction to ballet at a point in life when her body was past any dream of becoming a prima ballerina, and one of the indications that perhaps her mental struggles were more than simple symptoms of "too much" - too much alcohol, too many parties, too much attention, too much wild living and too little security.

We know how the story ends. But Fowler takes us on a route there that is strictly her own creation, while remaining utterly faithful to the sequence of events, letters, and notebooks of the main characters. And her style goes down like a bubbly drink on a hot summer day.

Comments